Virtual Viewing Room

Illumination:

21st Century Interactions with

Art + Science + Technology

Installation View

Illumination is grouped into three themes: Technology and The Touch Screen, Global Health and Discovery, and Climate Change and Sustainability.

Installation View

Technology and The Touch Screen: Featuring here (from left) Young Joon Kwak, Justin Manor, and Caitlin Cherry

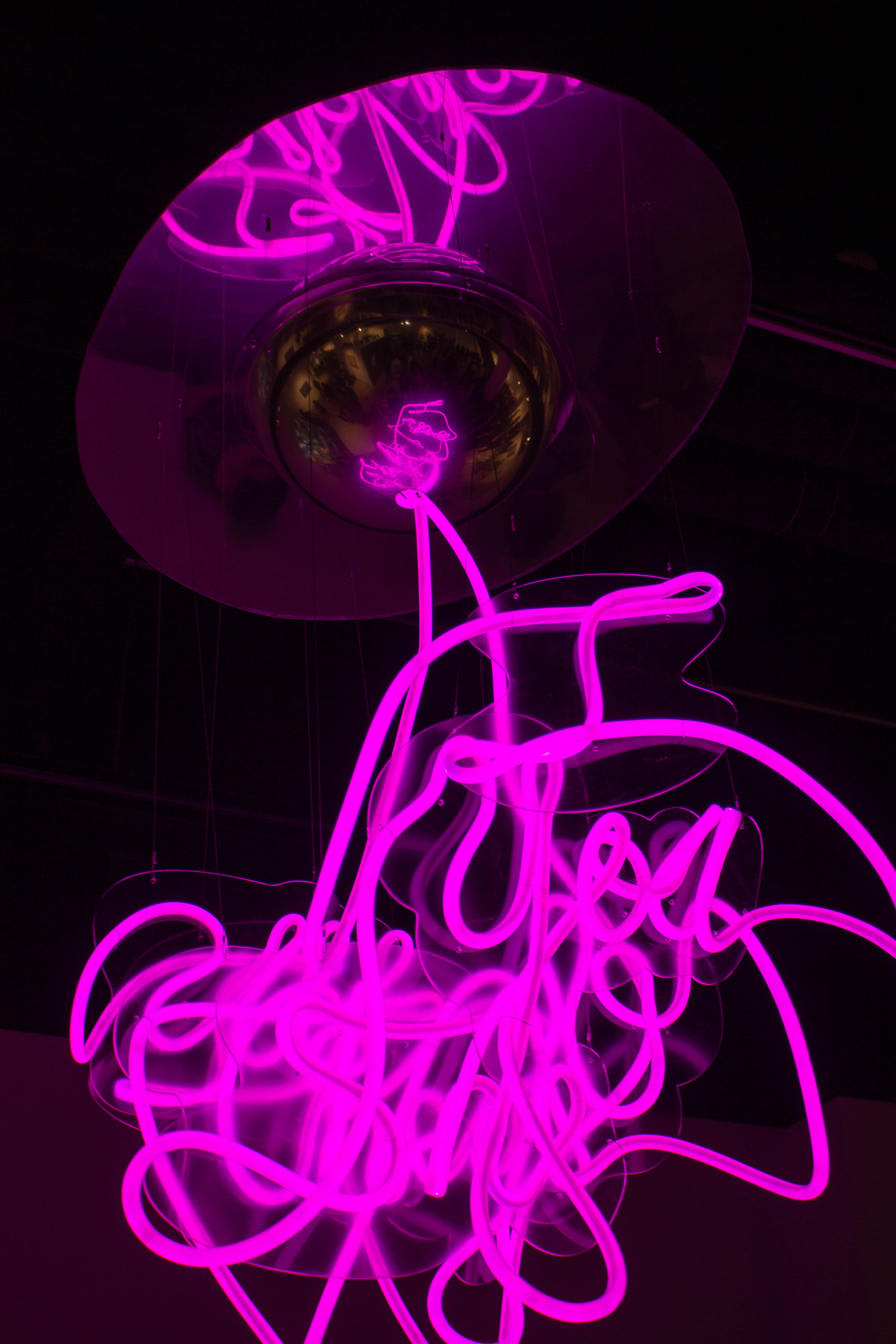

Young Joon Kwak, Shining Palimpsest

Three objects by the Los Angeles- based artist Young Joon Kwak deal with language, gender, and marginality. All are linked by the concept of surveillance. And all three artworks consider how we see ourselves, how we are seen by others, and how perceptions shift based on presumptions of the viewer, the viewed, and what we are assured is neutral technology. Kwak takes a composite approach to reimagining materiality, functionality, and form in order to propose different ways of viewing and interpreting bodies and the physical and social spaces in which we live. The term palimpsest is applied to written material partially or completely erased to make room for another text. Shining Palimpsest literally spells out seven personal pronouns (I, you, she, he, they, we, it) written in LED rope that physically wraps and twists over itself. Who we are and how we are viewed depends on perspective, including that of the surveillance mirror to which Shining Palimpsest is attached because, at some level, we are all being watched.

Young Joon Kwak, Surveillance Mirror Vaginis

Surveillance Mirror Vaginis more specifically references sexuality and gender mutability. Yet the large domed mirror at its core plainly reflects the environs and chronicles who is watching the goings-on.

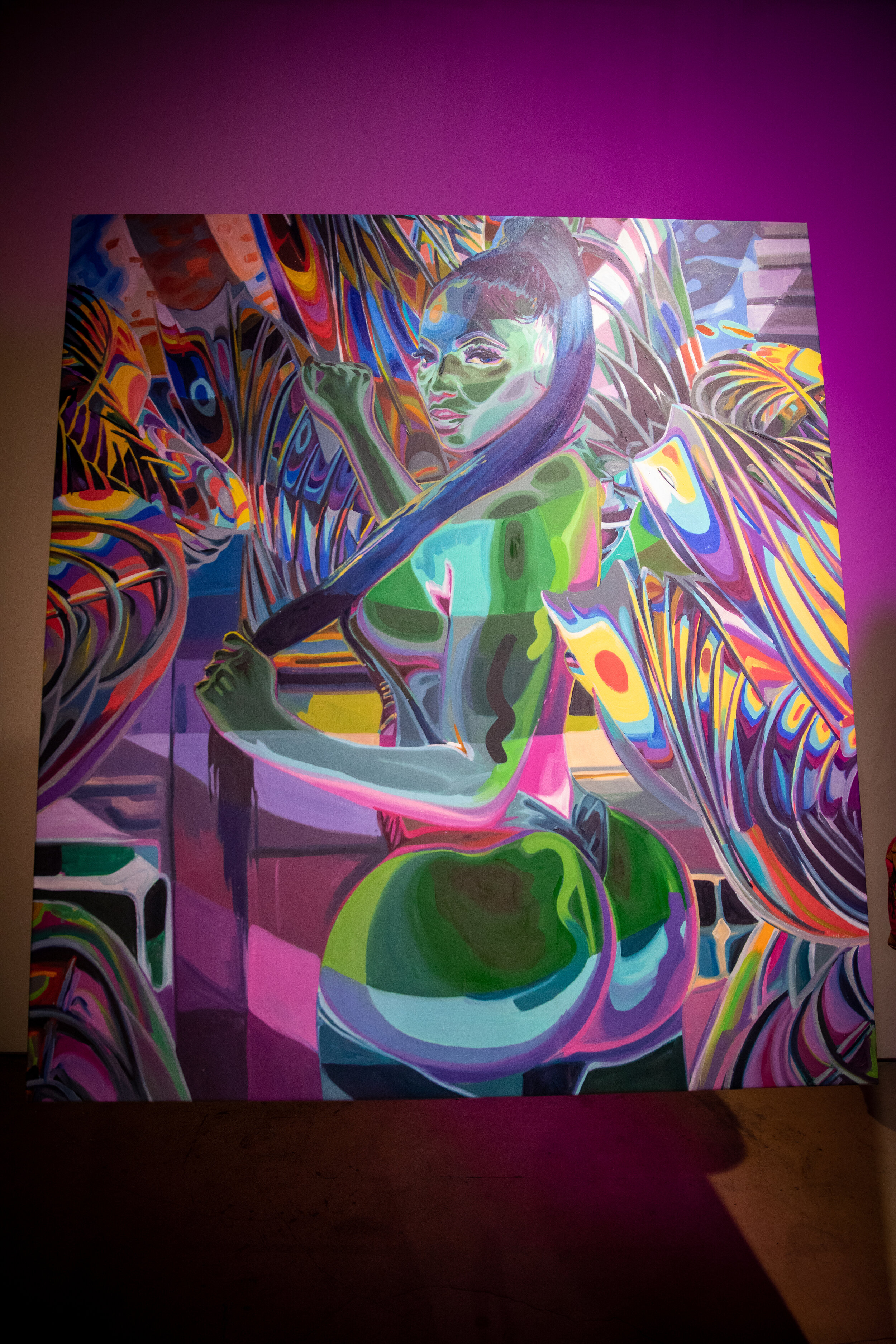

Caitlin Cherry, Axiom

In the year 2020, contemporary culture is created, enhanced, morphed, and/or condemned by electronic screen. Paradoxically, a stationary version of that screen becomes the medium by which Caitlin Cherry archives and the present. As a keen observer of the world, and as someone concerned with the transit of time and the shortness of memory, Cherry wants to record current culture that might be forgotten or discarded. Caitlin Cherry says that her paintings “have been inspired by phenomena and how we experience screens, especially Liquid Crystal Display (LCD) screens that are common with laptops and phones.” Beginning with pop culture imagery, particularly black women who might be rappers, cancer survivors, Instagram influencers, exotic dancers, or any woman who achieved momentary celebrity or notoriety, Cherry paints their image as it might be displayed on an LCD screen. But she paints those screens as if they’ve been impacted by the quirks and oscillations of technology, with distortions of color and appearance. It is a warped image waiting to be resolved. To further the bond between her paintings and LCD displays, Cherry mounts her large renderings as if they were a screen installed over a desk. Paintings are attached to a mobile metal support, so they can be flipped, rotated, or otherwise angled to a custom position. Whereas paintings are typically fixed to the wall as if they were windows into another reality, Caitlin Cherry’s flat screen paintings have the ability to both move and record time.

Courtesy of Luce Gallery

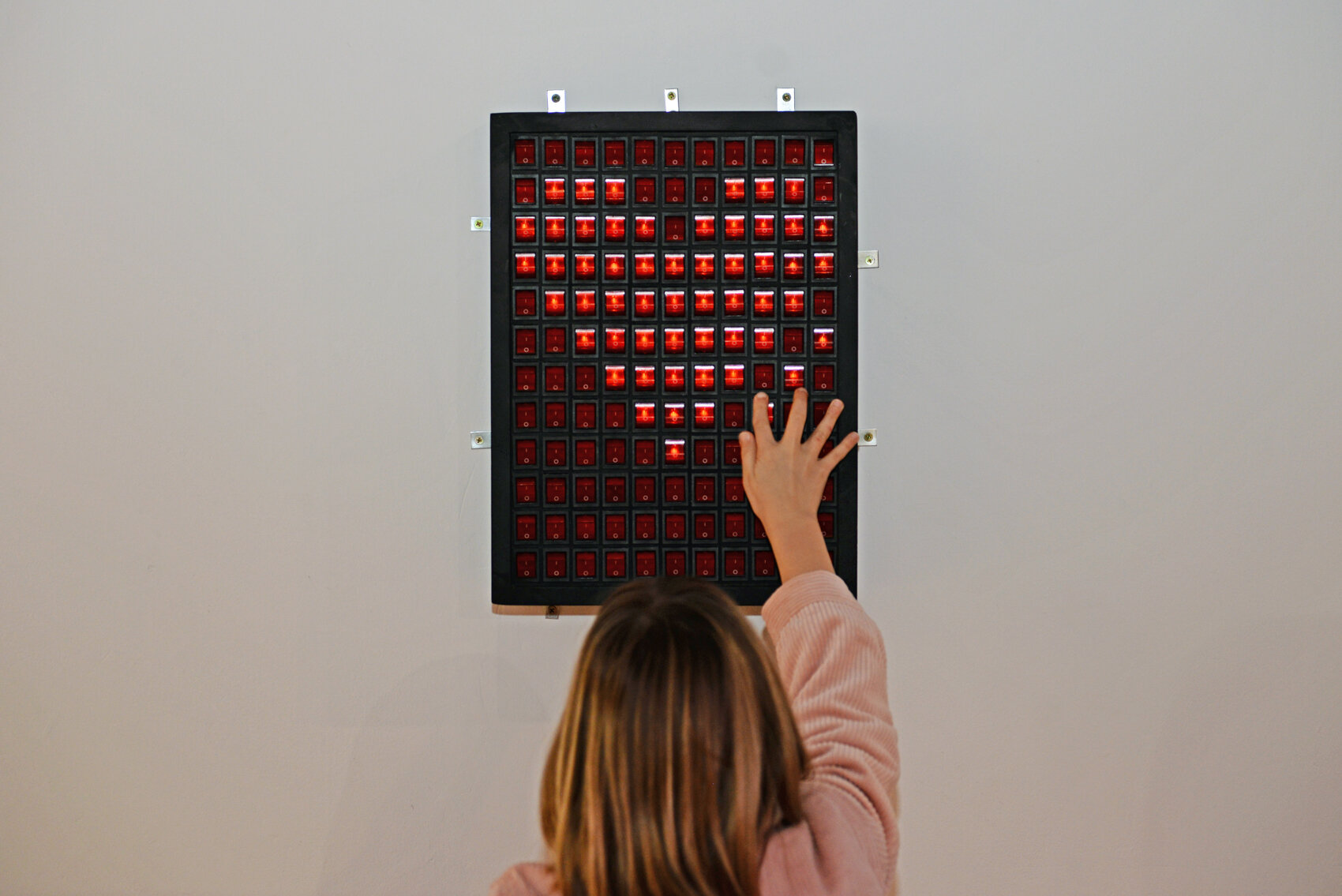

ELSOLDELRAC, LUMINO-INTERACTION: Memory of Touch

In his artistic practice, ELSOLDERAC creates objects that serve as evidence of their times. He does so as he shapeshifts from builder to designer to poet to theorist. For ILLUMINATION, ELSOLDERAC wants to reinforce the notion that while technology may or may not be our friend, it’s definitely worth playing with.

As background to his artwork for ILLUMINATION, ELSOLDERAC notes that technology has invaded our lives, become a part of our everyday activity, and undertakes a considerable amount of work for us: Turn on the lights! Play NPR! Keep the heat at 70 degrees!

Notwithstanding the burden that technology accepts for making our lives better, most of us simply don’t think about the other side of the arrangement: Just how does technology feel about being used so insistently by humans? Sure it’s a bit of personifying and even sentimentalizing our interaction with inanimate objects. Yet with all the research and advances in Artificial Intelligence, do we have any idea how long it will take for insensate objects to become semi-sensate?

To prepare civilization, ELSOLDERAC wants us to begin the process for making friends with solid matter now. Is he doing this because he’s accepting increasingly conscious technological co-existence as an evolutionary option? Truthfully, we don’t know. What is possible to know is that in LUMINO-INTERACTION: Memory of Touch, ELSOLDERAC wants to raise consciousness about our coexistence with technology. He wants to provide an opportunity to consider deepening your relationship with electronic devices by having a hands on experience with his light switch.

Justin Manor, FINFET Macro

Scientist Pairing: Shadi Dayeh, PhD, Qualcomm Institute/Calit2

Much examination and exploration regularly occurs at the nano scale, wherein a sheet of paper is around 75,000 nanometers thick, a nanosecond is one-billionth of a second, and miniaturization technology has so reduced the size of transistors that a billion can fit on a fingernail. Yet as technology advances, there is a need for these small transistors to become ever smarter. For Dr. Shadi Dayeh, the problem is how to correct the imperfections encountered as transistors shrink. Justin Manor has an insatiable curiosity about advanced technology and is especially attracted to the creation of new physical and electrical realities that might not find their way to market for 10 or 20 years. With his background in physics, media, and technology, Manor has created an artwork that takes the nano-scale surface of one of Dr. Dayeh’s new transistors and magnified it to a colossal scale. He has done so to make the unseen visible, to replicate an infinitesimally small on/off switch as a heavy metal object, to travel from nano to macro to see the detail in objects typically invisible.

Cy Kuckenbaker, Chromosome 22

Scientist Pairing: Zbigniew Mikulski, PhD, La Jolla Institute of Immunology

With recent advances in microscopy techniques, it’s possible to see right down to the level of single molecules. Dr. Zbigniew Mikulski is an expert in imaging methods that show how cells move around, communicate, live, and die in real time. He is working to discover the mechanisms of disease, because understanding those mechanisms can lead to intervention. On encountering the microscopy lab at La Jolla Institute for Immunology (LJI), Cy Kuckenbaker concedes to a strong emotional impact, one in which he experienced biology in a way that felt like astronomy. “The world they’re exploring is three dimensional, inconceivably vast...and breathtaking.” Kuckenbaker received basic training in the use of a microscope in the LJI lab and subsequently filmed what he saw through the microscope. After working with and editing the raw footage, he created a 36 second video for ILLUMINATION of living human cells as they were dividing. Kuckenbaker also came away from his encounter with a sense of astonishment at the scope and complexity of life, including an awareness that every single cell of the human body contains information so vast as to be inconceivable. To make that point, Kuckenbaker’s installation includes a printout of some 10,000 pages of a data sequence that occurs in the nucleus of Chromosome 22, the smallest of the 23 human chromosomes. Most cells in the body contain the full set of 23 chromosomes, and an average adult human has trillions of cells. Finally, to recognize and honor Dr. Mikulski, Dr. Sarah McArdle, and others who worked with Kuckenbaker for his installation, the artist created wallpaper which portrays repeated images of the scientists at work.

Alexander Kohnke, cross hatch 01-04

Scientist Pairing: Dmitry Lyumkis, PhD, Salk Institute

Since the advent of the microscope several centuries ago, there has been continuous effort to develop increasingly finer degrees of resolution. We are now at a point where we can visualize the precise organization of atoms within individual proteins. Dmitry Lyumkis, in his work to understand how HIV creates a permanent infection in target immune cells, conducts his study by freezing proteins at cryogenic temperatures and, using a transmission electron microscope (which relies on electrons instead of light), he can then image the frozen samples at very high levels of magnification. For Alexander Kohnke, the change in scale was riveting. It was about the seemingly magical ability of making something visible that’s not just invisible to the human eye, but until just a few years ago, would have been invisible to science as well. What Kohnke has done for ILLUMINATION is to rescale a small object and, in doing so, turn it into something else. Within the forest, Kohnke found several barn owl pellets, which are regurgitated masses of undigested parts of an owl’s food that can include insect exoskeleton, undigested plant matter, fur, etc. Kohnke then photographed and greatly enlarged these pellets, essentially transforming them into what looks like something else entirely, perhaps landscapes or building profiles or creatures with their own personality. “Magnification changes your sense of the world,” Kohnke says. “The amount of detail in small things is amazing. There is so much we don’t see in the world because it’s not easily visible.” And when you enlarge it, it can become something else entirely.

Becky Robbins, Leap of Faith

The term “process” describes a series of actions directed to some end. Artists like Becky Robbins employ a process that parallels one used by scientists and technologists. It begins with an idea or image which then gives rise to questions that become the subject of study and research. Links and connections among the various elements of study crop up; sometimes they’re obvious, vague or unexpected. Throughout the process though, the constants are on-going curiosity, commitment, and attention. In the end, though, the results may or may not have been anticipated. Robbins begins her work with specific imagery in mind. Those images are often but not exclusively from the natural world and, as seen in Leap of Faith, include flowers, birds, trees, plants, and animals. Each element becomes the subject of inquiry and study well before its painted. “I prefer to paint optimistically,” she says. “I don’t want to add more fraught art to the world. I think we need to have hope, be part of the world, and participate in our own rescue.” Robbins interlinks the dominant images them because she strongly believes that everything is ultimately connected. A body is a whole, a system, not simply its discreet and distinctive parts. Associations and networks are made to create a single whole.

Dia Bassett, Maternal Source

Scientist Pairing: Reza Ghadiri, PhD, Scripps Research

Human beings have coevolved with microbes that live in and on us. The largest concentrations of symbiotic microbes reside in our gastrointestinal tract and are referred to as the gut microbiome. It is comprised of hundreds of bacterial species that, with other microbes occurring elsewhere on the body, together function as a distributed organ. Dysfunction of the gut microbiome impacts the onset and progression of several diseases, including heart disease, diabetes, and disorders such as depression and migraines. Clearly, a healthy gut microbiome is essential to well-being. In her discussions with Dr. Ghadiri, Bassett was most intrigued with an illustration of the human body showing the anatomical locations of different strains of bacteria that make up the microbiome. There are an estimated 30-50 trillion bacteria cells on the human body, far outnumbering actual human cells. As a new mother, Bassett was particularly drawn to the five areas of a woman’s body that most strongly influence the microbiome of infants delivered through natural birth, nursing, touching and kissing, i.e., those that inhabit the mouth, gut, breast, skin, and vagina of the mother’s body. Bassett tries to capture and emphasize the importance of the microbiome in these five areas through the use of buttons, brightly colored ribbons, yarn, and fabric, all of which represent the variety of bacteria that form the microbiome of our bodies.

Installation View

Global Health and Discovery: Featuring (from left) Akiko Surai, Griselda Rosas, and Bhavna Mehta

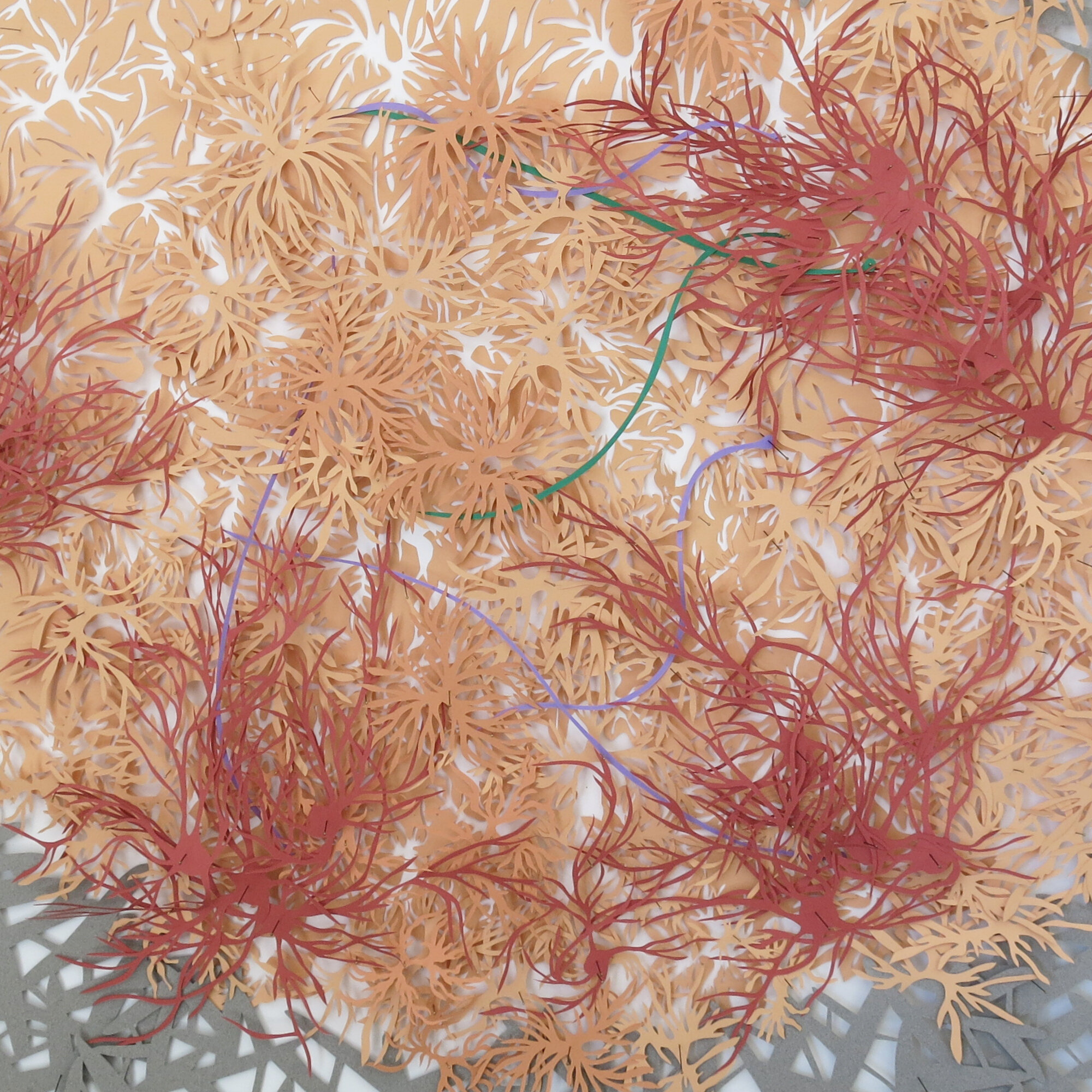

Bhavna Mehta, Fault Lines

Scientist Pairing: Sam Pfaff, PhD, Salk Institute

The precision of our movements is often taken for granted – until we have a personal experience with stroke, spinal cord injury, or a disease such as Polio, Parkinson’s, or ALS. Each of these conditions affect the nervous system differently and each illustrate how multiple sites within the brain and spinal cord are involved in controlling movement. Bhavna Mehta is herself affected by polio, a spinal cord disease that starts with a virus. Through a series of meetings with Dr. Pfaff and close work with PhD candidates Ben Temple and Peter Osseward at the Salk Institute, the artist studied slides of spinal cord cross-sections, becoming aware of the scale, complexity, and the monumental challenge of treating spinal cord injuries such as her own. As an artist who cuts and manipulates paper to dazzling effect, Mehta’s experience at Salk led her to create a colossal 20-foot wide representation of a cross-section of the spinal cord. She portrays different types of neurons within the spinal cord which connect and communicate with one another. Because the spinal cord is symmetrical – each side controls one side of the body – the artist uses deepened color and increased material density to show substantial activity on one side of Fault Lines, and static behavior on the other side. Fault Lines is akin to looking through an atomic microscope and witnessing molecular forces at work.

Griselda Rosas, RASA

Scientist Pairing: V.S. Ramachandran, PhD, UC San Diego

For Griselda Rosas, meeting Dr. V. S. Ramachandran at the Center for Brain Cognition had the elements of an epiphany -- a moment of insight and discovery, “as if Dr. Ramachandran is my soul mate,” Rosas says. The connection for Rosas is Ramachandran’s broad interests having to do with the neural basis of human behavior. He raises the possibility of uncommon associations, like synesthesia, e.g., when a response produced through stimulation of one of the human senses such as hearing, seeing, smelling, or tasting, creates a response in an entirely different sensory modality. Experiences vary widely but examples include when certain sounds induce visualizations of colors, when letters of the alphabet invoke certain smells, or literally feeling what another person is experiencing, such as a tap on the shoulder. Rosas believes many artists “see beyond the thing itself,” and that she herself uses experience to create poetic referencing in her artwork. Rosas was most affected by Ramachandran’s concern with post-colonial legacies, the experience of phantom limb syndrome, and the multiple forms and configurations of synesthesia. She has channeled that experience into RASA, where she is addressing in metaphoric terms the chaotic breakdown of class structures after the colonialism and territorialism that overtook both India and the New World.

Installation View

Featuring (from left) Anne Mudge and Akiko Surai

Akiko Surai, Untitled

Scientist Pairing: Krishna Vadodaria, PhD/ Gage Lab, Salk Institute

Drs. Gage and Vadodaria study psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases of the human brain; they are particularly interested in discovering the progression and mechanisms of brain cell dysfunction. In conceiving her Untitled piece, Akiko Surai was impressed by how the Gage Lab was able to take a human skin cell and, through a series of processes, reprogram it to be a neuron. Surai felt this creative repurposing was a great parallel to her own use of “decorative” embroidery stitches to mend mesh netting. Moreover, as part of Dr. Vadodaria’s research, a multicolored dye process helps differentiate structures within a cell, e.g., so that one type of dye will bond to DNA. On seeing how dye concentrates within portions of a cell, the artist developed ideas for her color palette and arrangement of stitches. Surai says that she started to think of her stitches as the different structures inside a cell. “As I stretch the mesh over the plexiglass I think of it as a pristine microscopic slide ripe for experimenting. I imagine how my stitches might develop and divide to spread across the surface in distinct stages. This gave me the freedom to experiment with new stitches and expand the vocabulary of my embroidery.” Surai uses stitchery and embroidery to mimic a complex and interconnected organism — like the human brain — that might tear and stretch, grow fragile in some areas, remain dense and robust in others, yet ultimately function as an integrated network. It is an artwork that reflects impairment, change, intricacy, and wholeness.

Anne Mudge, Sixteen x2m

Scientist Pairing: Ferhat Ay, PhD, La Jolla Institute for Immunology

While science is full of mysteries, Dr. Ferhat Ay is working with a particularly enigmatic one. His field is bioinformatics which looks into the geometries of genome architecture. Strands of DNA, which measure about two meters when fully extended, are somehow packed within a cell’s nucleus which is a million times smaller. Our genes are made of DNA, and that DNA is dynamically “folded” inside the nucleus. Depending on what part of the DNA is exposed by how it is folded ultimately determines whether a skin cell or muscle cell is created, or whether a person has a greater or lesser vulnerability to disease. Understanding how this works can revolutionize our understanding of how genetic variants are linked to specific human traits and disease probability. Anne Mudge is not intending to replicate the actual folding and compression process, but rather is working with geometries of folding, twisting, coiling, and looping that occur within the cells. She does so with stainless steel wires, each of which is two meters in length, and results in abstract forms that have more randomness than she typically employs. Some of the loops and folds are tight and dense, and some furl energetically out into space, all of which Mudge imagines is happening dynamically within the nucleus itself. Ultimately, she says that while the geometry is a bit more chaotic, it resolves itself because she fits them into spherical shapes to suggest shell-like or nucleus forms.

Margaret Noble, Dogma Roulette

Scientist Pairing: Matthias von Herrath, PhD, La Jolla Institute for Immunology

Scientific endeavor is not immune to human vulnerabilities. Of distinct concern to Dr. Matthias von Herrath in his research is the insistent role of dogma. Dr. von Herrath notes that, “Science is considered to be based on facts, flawlessly rational and logical, where hypotheses are either independently verified or refuted by evidence. Yet, some ideas can become so entrenched that they effectively turn into articles of faith and stall progress.” He says, “the biggest threat to science is that we hold onto ideas too closely.” Margaret Noble has created a game for visitors to play, hoping it will help us consider why we believe what we do, why we believe there is a single answer to all questions, and how the belief in dogma so influences our world view. In Margaret Noble’s custom-made gaming construct, all is determined by a spin of the roulette wheel to let you know that your belief has been validated, discredited, or made irrelevant by chance.

Margaret Noble, Dogma Roulette

Detail

Margaret Noble, Dogma Roulette

Detail

Trish Stone, Network Error

Trish Stone employs contemporary technology to speak to human disconnectedness in an increasingly digitized and technological society. Her work for ILLUMINATION began with a 3D scan of herself at the Prototyping Lab at Calit2 at UCSD, which produced about 100 “Tiny Trishes” using a 3D printer. Each Tiny Trish was about 5” tall and hand painted by Stone. Protest signs were produced for the Tiny Trishes to hold (Burn It All Down!, It’s Just C++!, We Were Promised WiFi!), and figurines were placed around San Diego’s North Park neighborhood in front of banks and within public places. Then the miniatures were photographed on site.

Trish Stone, Too Little To Fail

Trish Stone, Something is Wrong

Installation View

Global Health and Discovery: Featuring (from Front to back) Tim Murdoch, Hugo Heredia Barrera, Becky Guttin, Beliz Iristay, Amy Yao

Tim Murdoch, Just Nod if You Can Hear Me

Scientist Pairing: Vikash Gilja, PhD, Qualcomm Institute/Calit2

Electrochemical neural activity in the brain allows us to sense, perceive, think, decide, and act. As our understanding of this process evolves, and as advances in technology continue, Dr. Vikash Gilja is working to develop communication systems between brains and machines. One of his goals is to have thinking control increasingly complex prosthetic limbs. Tim Murdoch has always had an affinity toward the sciences. He believes that scientists and artists share certain characteristics: Both must be creative and have an inventive spirit, an intense curiosity, and a desire to understand the world through differing methodologies. Just Nod If You Can Hear Me is a construction of tree limbs, effectively a stand-in for body parts, that are fitted with sensors. The heart of the artwork is a microprocessor covered in paper made from shreds of Murdoch's personal papers. It is effectively the brain of the piece. When someone walks close by the tree limbs, proximity sensors trigger an impulse that’s sent to the microprocessor heart. And a doorbell rings. “Sometimes,” Murdoch says, “human connections begin with just a ring at the door.”

Hugo Heredia Barrera, Changes and Damage of DNA on a Cancer Cell

Scientist Pairing: Vipul Shukla PhD/Rao Lab, La Jolla Institute for Immunology

A major motivation for the Rao Lab's research is to understand the mechanisms by which cancers originate. The goal is to design specific treatment strategies against cancers and, ultimately, to prevent the development of cancers altogether. With a background in crafting and experimenting with scientific glass, Hugo Barrera’s initial impression was how inspirational Dr. Vipul Shukla’s dedication was, and secondarily, that Shukla uses glass equipment that looks like Barrera’s own. As the scientist and the artist went deep into discussing DNA damage that occurs as a result of cancer, Barrera’s own thoughts recognized the fragility shared by human cells and glass itself. In Changes and Damage of DNA on a Cancer Cell, Barrera attempts to demonstrate the impact of cancer on a human cell and show how the cancer, expressed by the threads of steel in his artwork, enrobes a healthy human cell. The white and blue plastic mesh represent the DNA, connecting the glass cells to one another. Crystal clear glass cells are healthy; cells covered with wire are infected. “I want people to see how delicate and sensitive and strong cells are,” Barrera says, “and how, like glass, they can break at any moment.”

Installation View

Featuring (from front to back) Becky Guttin, Beliz Iristay, Amy Yao

Becky Guttin, Clean - Dirt - Dust

Scientist Pairing: Lu-Lin Jiang/Huaxi Xu Lab, Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute

Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) was identified in 1906 when a woman who had died of a mental illness was found to have abnormal clumps of beta amyloid plaques in her brain. Since then, AD has risen to become the most common neurodegenerative disease, affecting over 3 million Americans yearly, and at this time, is an irreversible and progressive brain disorder destroying memory and general brain functions. The accumulation of toxic amyloid clumps in the brain of AD patients indicates the occurrence of neuronal damage. After meeting with Dr. Jiang, Guttin recalls hearing words repeated over and over: clean, dust, dirt. The beta amyloids accumulating in the brain added “dust” to brain cells. As “dust” accumulated, what had been “clean” became jammed with “dirt.” It meant creating an artwork that represented a direct metaphor to the process of going from normal to diseased. The artist started working with pieces of used aluminum and compacting them into squares of various sizes. The thin line of grass was meant to represent health and life. But the symbol of neuron degeneration is the tree, though standing and alive, accumulated dirt shown as parts of its branches covered with aluminum. The artwork is an allegory of AD in progress.

Becky Guttin, Clean - Dirt - Dust

Detail

Beliz Iristay, building

Scientist Pairing: Deniz İlkbaşaran, UC San Diego

The Mayberry research group on multimodal language development that Dr. Deniz İlkbaşaran is a part of studying the long-term effects of late first language learning on deaf people’s language outcomes. They investigate how deaf people in the United States who have learned American Sign Language (ASL) at various ages process, understand and produce ASL. Combining behavioral and brain imaging methods, the Mayberry group shows that depriving or delaying deaf children of sign language learning has significant outcomes on how the brain organizes for language. Deaf adults who learn ASL early in life use similar brain areas to process ASL as hearing adults do for their native spoken language. On the other hand, missing the necessary linguistic foundation early in life alters the neural structure and pathways that adults use to process language, and has longterm effects on the mastery of complex grammatical sentence constructions. Dr. İlkbaşaran worked with artist Beliz Iristay and together the two imagined a sculptural installation using Mexican adobe bricks with different handshapes from American Sign Language (ASL) as its building blocks. On one side of the wall created for ILLUMINATION are ASL handshape impressions, starting with simple and early acquired handshapes at the bottom, progressing upward to more complex and advanced ones, some of which begin to resemble numbers, letters and signs in ASL (e.g., FAMILY, SUPPORT, WHY?, HOW?, SCIENCE, ANALYZE, RAINBOW). On the other side of the wall, through designs and patterns, Iristay provides a visual interpretation of her research with Dr. İlkbaşaran.

Sheena Rae Dowling, More

Scientist Pairing: Oliver George, PhD at UC San Diego

When scientists began studying addictive behavior almost a century ago, most did so under the influence of a powerful myth: That people addicted to drugs were morally flawed and lacking in will power. Since then, groundbreaking discoveries about the brain have revolutionized the understanding of compulsive drug use. Research has shown that addiction is actually a disorder that is enhanced by a person’s distinctive genetic variation. It can mean a complete rewiring of brain function so that an individual focuses entirely on satisfying the dependence/obsession. Sheena Rae Dowling speaks of spending time with Dr. Olivier George in his lab and seeing a scan of a healthy brain. In that scan, areas of the brain were lit in different colors to show distinct functional regions, all operating in an independent but interconnected loop. In contrast, a brain scan of an individual suffering from addiction — perhaps cocaine, nicotine, or alcohol — showed the entire brain lit in a single color, revealing that one sector of the brain hijacked the entire brain, and all brain functions were supporting the need to satisfy the addiction. For Dowling, the image was riveting. It became the basis for her piece More, in which panels show an intricate swirl of colors that glow in a complex and integrated manner, much like the sophisticated working of a healthy brain. But on receiving a sudden stimulus — at the press of a button — normal rhythmic functions cease and all panels are taken over by a stationary red color. It’s akin to a brain in withdrawal, with every sector pleading, insisting, and commanding that it be provided more stimuli.

Sheena Rae Dowling, More

Sheena Rae Dowling, More

Sheena Rae Dowling, More

Installation View

Climate Change and Sustainability: Featuring (from left) Amy Yao, Danielle Dean

Amy Yao, Intercontinental Drift No. 1

Intercontinental Drift No. 1 is about what lies beneath. Contemporary commerce promotes the routine transit of cheap goods across the oceans and the sky, and eventually those goods invade our lives thoroughly and anonymously. We, blissfully oblivious to the invasion, are encouraged to believe in the innocence of consumerism. We remain unaware of the impact of our most mundane actions in creating pollution or contamination thousands of miles away. Because we don’t see the direct consequence of our actions, we bear no responsibility. Intercontinental Drift No. 1 literally installs a window in the wall to make visible what’s normally out of sight. What it displays is a growing environment filled with implications we chose to ignore.

Courtesy of Various Small Fires, Los Angeles

Amy Yao, Doppelgängers

An alert pops up on Facebook warning of a health threat. Is it genuine or bogus? Is it a public alarm or are you being specifically targeted? Whatever your response, is it paranoid or prudent? Is there a threat to global health? Amy Yao, an American artist of Chinese descent, received a Facebook alert advising that rice from China was contaminated with plastic and making people sick. Then she received a written notice that the ground beneath her art studio might be contaminated with lead from a nearby industrial plant. As she discovered, the Facebook alert was false, an episode of anti-China fear mongering, and the lead notice was authentic. But the two incidents, coming within the same time frame, revived in Yao the predicament of distinguishing between authentic and invented.

Courtesy of Various Small Fires, Los Angeles

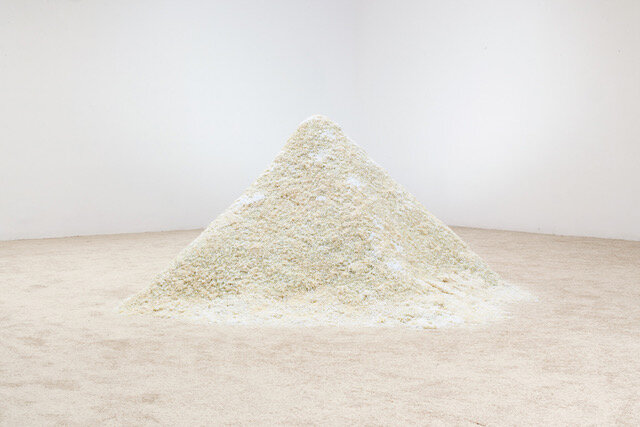

Amy Yao, Doppelgängers

Doppelgängers, a mound of rice mingled with assorted debris, is her monument to the incident: it is a ghostly double of what appears real from afar but close up is fake.

Courtesy of Various Small Fires, Los Angeles

Danielle Dean

Asset No. 1 (Ford V.8, 1937),

Asset No. 2 (Ford V.8, 1937),

Asset No. 2 (Bold new world on wheels, Ford, 1957),

Asset No. 2 (Movement of men and Materials, 1931),

Asset No. 1 (Interior of the Service Building at Ford Motor Company , Detroit, MI, 1915,

Albert Kahn and rubber tapping in Fordlândia,Brazil)

Assets No. 2, 3, 4 (Some of its best friends live in the west, Ford, 1940)

Danielle Dean explores the colonization of the mind and body by media and culture. She is concerned that many people develop a mindset about the natural world through commerce and marketing. That is, when presented with a consumer’s perspective of the world, we see the natural environment as raw material to be used any which way. In her recent artwork, Dean researched Fordlandia, a district established by Henry Ford in the Amazon Rainforest in 1928. It was an industrial town intended as a source of rubber for Ford’s automobile manufacturing. While the project failed and was abandoned in 1934, the subject captivated Dean. Thereafter, she examined animated advertising used for Ford cars and was drawn to the way landscape became a device chiefly intended to enhance vehicle acquisition.

In 2019, Dean created Long Low Line (Fordland), a video in which she drew images from advertising and commercials used by the Ford Motor Company. For her video, she separated elements of the illustrations — cars, mountains, streams, trees, forests, etc. — so that she could layer those images to replicate a process once used by Walt Disney Studios to give an increased sense of depth to two-dimensional artwork.

Her work for ILLUMINATION reflects Dean’s research and environmental concern. Featured are several stills created for Long Low Line (Fordland), wherein elements of the landscape are created on separate layers — in effect, isolating them as merely background for the promotion of the automobile. Adorning several of these images are stickers in the shape of the bugs that ate the rubber trees at Fordlandia.

Installation View

Climate Change and Sustainability: Featuring (from left) William Feeney, Yasmine Kasem, Jason Lane

William Feeney, Exposing the questions which have been hidden by the answers

Scientist Pairing: Ben Frable, Scripps Institution of Oceanography

William Feeney is very clear about wanting his artwork to function on many levels. Even so, the most obvious level is the immediately visible one: he has created a life-sized full grown Great White Shark, turned inside out. Feeney has long been fascinated by large sharks and human relations with them. Fostered by popular culture, sharks have become a source of primal fear for many people. Simultaneously, and especially now, sharks are recognized as vital to the ecosystem we inhabit. And thus Feeney points to a built-in conflict: we want to save the oceans, but we’re scared of sharks. William Feeney’s creation is something of an artistic conflation of anatomy and taxidermy. He salutes the support he’s received in completing his creation, including Dr. Greg Rouse in the Marine Biology Research Division of SIO, Dr. Allison Bronson, a white shark expert from the Department of Biological Sciences at Humboldt State University, and the stunning opportunity he had to attend a necropsy of a Thresher shark. Ben Frable, Marine Vertebrate Collection Manager at SIO, noted that Feeney “really pushed my knowledge of internal anatomy to the limit, especially when thinking about how it would look inverted. Probably one of the most difficult aspects to capture was what the famous ‘Jaws’ looks like from the inside. To help, we examined the partially dissected jaws from an Oceanic Whitetip Shark collected in 1955 off Isla Clarion, Mexico. It is fantastic that 64 years later, this shark helped inspire and inform” this artwork.

William Feeney, Exposing the questions which have been hidden by the answers

Detail

William Feeney, Exposing the questions which have been hidden by the answers

Detail

Yasmine Kasem, al Zahab al Abiad/Kanz Siti - White Gold/Grandma’s Treasure

Yasmine Kasem’s artwork appears deceptively simple — yet it contains countless allusions and references, many that are deeply personal, and all of which denote the precariousness of our times and the inherent difficulty in maintaining equilibrium and sustainability. At the most private level, Kasem is connecting to her heritage as an Egyptian Muslim woman who, though born and raised in Indiana, works almost exclusively with Egyptian cotton just as her grandmother did in North Africa over a hundred years ago. Yasmine cleans and combs the raw cotton, then fashions and folds it, ultimately rolling the sheets of cotton into round bales resembling the hay bundles used to feed livestock on Indiana farms. Some of Kasem’s cotton bales display remnants of the Indigo tattoos which adorned her grandmother’s face, as an homage to a woman the artist never met but, through her work, feels a deep connection with. At the public level, Kasem is balancing bundles of cotton — the white gold of the title — one bale on top of another, free of structural links, made ostensibly steady, but subject to wobbles and tilts and potentially even collapse, all of which notes the flux and uncertainty present in every attempt to maintain what we treasure. Environmental sustainability, like familial sustainability, is an uncertain endeavor.

Jason Lane, Untitled 90 ton pressing #1/#2

Scientist Pairing: Wolfgang Busch, PhD, Salk Institute

Despite the importance of root systems to plant sustainability, it is not well understood how a root system’s growth and response to diverse environmental conditions is encoded in the plant genome. Dr. Wolfgang Busch aims to help plants grow a bigger and more robust root system that can absorb larger amounts of carbon to help fight climate change. Dr. Busch makes use of the flowering plant Arabidopsis thaliana, commonly known as thale cress, generally considered a weed and often found along roadsides and in disturbed lands. Given the use of this wild plant in important scientific research, artist Jason Lane sought to ennoble and elevate the importance of A. thaliana, particularly after seeing antique plant illustrations from the 19th Century. Lane notes he was “filled with contradictory emotions of shared interest and hope, along with a strange unreasonable empathy for the plants undergoing this process.” For ILLUMINATION, Lane employed a 90-ton metal forming machine and custom manufacturing die to directly press A. thaliana into heavy rag paper, virtually combining the plant and the paper into a single unit. It is a gesture of honor.

Jason Lane, Untitled 90 ton pressing #1

Detail

Janelle Iglesias, gestures of living

Human beings have a complicated relationship to nature. Most think the natural world is beautiful, often awe-inspiring, sometimes frightening, certainly vast and spectacular, dependably present, and typically just beyond the front door. And yet it’s evident that nature is also for the taking, abusing, and artificializing. Consider the impulse to avoid responsibility for a living plant, one that actually requires attention, in favor of a plastic plant that needs only intermittent dusting. Sculptor Janelle Iglesias takes familiar and everyday objects and removes them from their traditional context. She wants them to be seen anew, as if they were foreign and exotic items viewed for the first time. For ILLUMINATION, Iglesias selected artificial plants, faux flora for which she has both affection and aversion. “I’m not answering the problem of sustainability,” she has said, “but I’m pointing out our conflicted value system around the natural world.” To make plain the concept of tension with the natural world, Iglesias chose to live for a time with plastic plants. She thinks of them as objects that decorate our lives rather than objects with which we interact. So, she began her interactions with her fake plants by taking the omnipresent labels and bar codes off real fruit and vegetables and donating them to the leaves of her plastic plants. She says that “instead of watering it, I gave it stickers. I’m giving it a sign of life. I’m tending it.” And, perhaps, developing a bond with it.

Janelle Iglesias, gestures of living

Detail

Young Joon Kwak, Brown Rainbow Eclipse Explosion

Three objects by the Los Angeles- based artist Young Joon Kwak deal with language, gender, and marginality. All are linked by the concept of surveillance. And all three artworks consider how we see ourselves, how we are seen by others, and how perceptions shift based on presumptions of the viewer, the viewed, and what we are assured is neutral technology. Kwak takes a composite approach to reimagining materiality, functionality, and form in order to propose different ways of viewing and interpreting bodies and the physical and social spaces in which we live. Brown Rainbow Eclipse Explosion is quintessentially an exploded disco ball, slowly rotating. In obscuring light, the ball casts moving shadows that suggest all manner of new possibilities. However, the possibilities imagined depend entirely on the viewer. Once the viewer moves to alter their fixed and figurative point of view, the possibilities and imagnings alter as well.

About the exhibition

The San Diego region is home to cutting-edge scientific and technological research organizations. It’s also home to artists fascinated by new ideas and breakthrough pursuits.

We live in a time when microscopes make it possible to see the precise organization of atoms within individual cells. We can understand how some diseases create infection in immune cells, see cells multiplying in 3D environments that looks more like astronomy than biology, and understand how cells communicate, live, and die in real time. Research is underway to save lives, to reduce pain, to serve the planet, and to keep us from disease and degeneration.

Artists participating in ILLUMINATION have divergent take-aways from their interaction with scientists, technologists, and contemporary research. Some opt for artworks that serve as metaphors for the science they’ve encountered, some use the science as a stimulus to a creative journey they’re already engaged in, and all bring individual experience, a reflective attitude, and sometimes a deeply intimate history to their endeavor in spinning science into art.

Participating Research Institutions:

La Jolla Institute For Immunology | Qualcomm Institute | Salk Institute | Sanford Burnham Prebys Medical Discovery Institute | Scripps Research | Scripps Institution of Oceanography | UC San Diego

16 artists were paired with scientists from these institutions, curated by Chi Essary, and 10 artists worked independently, curated by SDAI.

Themes and Accompanying Soundscapes

Global Health and Discovery

Hugo Heredia Barrera

Dia Bassett

Sheena Rae Dowling

Becky Guttin

Beliz Iristay

Alexander Kohnke

Cy Kuckenbaker

Bhavna Mehta

Anne Mudge

Tim Murdoch

Margaret Noble

Becky Robbins

Griselda Rosas

Akiko Surai

Technology and The Touch Screen

John Burnett

Caitlin Cherry

ELSOLDELRAC

Young Joon Kwak

Justin Manor

Trish Stone

Climate Change and Sustainability

Danielle Dean

William Feeney

Janelle Iglesias

Yasmine Kasem

Jason Lane

Amy Yao

Photos by Elastic Lens Photography, Tim Hardy, Ariana Velazquez, Alex Matthews, Paul M Bowers